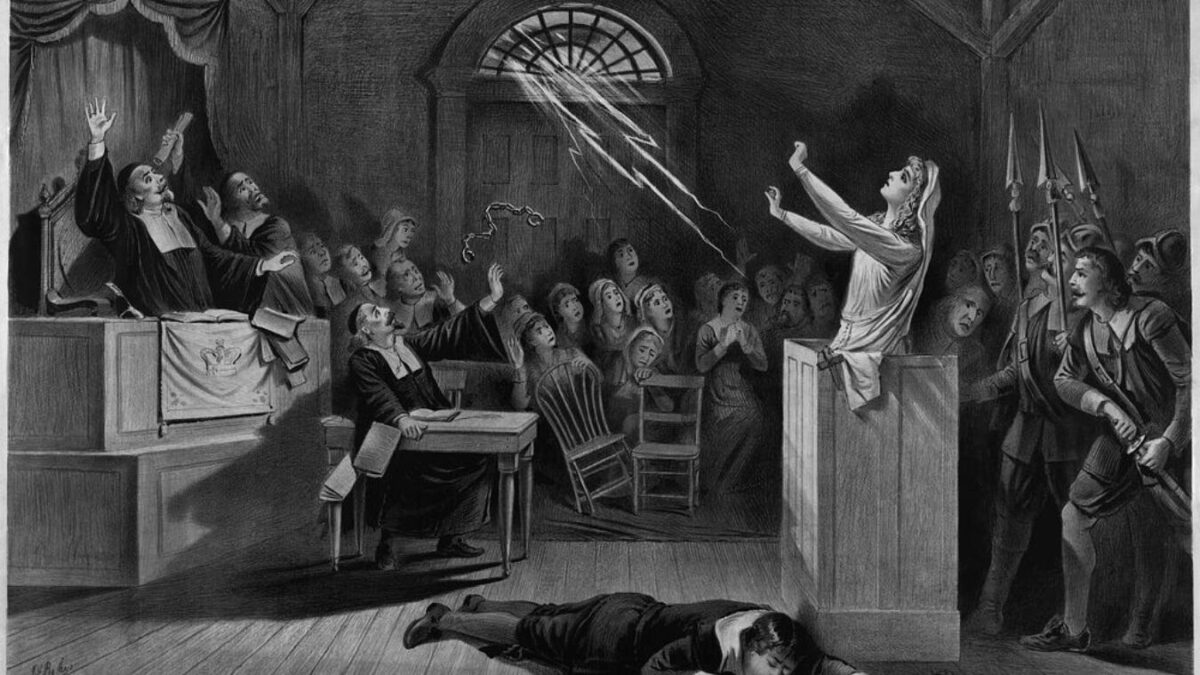

Halloween tourists are making their annual descent on Salem, Massachusetts to visit the real-life site of the supernatural on trial—the 1692 execution of 19 people for witchcraft. Piles of books and movies tell the Salem witch trial story, replete with wild-eyed, sexually repressed Puritan zealots roving the dark, foggy countryside seeking out women to drag into their evil court.

Although it’s no comfort to those who faced the gallows over 300 years ago, in fact, the made-for-Halloween scenes are largely based on centuries-old propaganda repeated by left-wing libertines today, who use it to push the myth that piety is bad and America was, somehow, rotten to the core from the beginning. The truth is the American colonies in 1692 were probably one of the safest places in the world to be if you were a woman—or even a witch.

Records indicate that at least 12,000 people were executed for witchcraft in Europe during the 17th century, although the estimates go as high as 300,000, during the so-called “Burning Times.” In England, witch executions had slowed down by the mid-1600s, but still, more than 250 women were executed. By contrast, the total body count in the American colonies, including the Salem witch executions, was 35.

Of course, early American colonists believed in witchcraft, just like their European cousins. About 200 people were charged as witches in the American colonies in the 17th century, but almost all of the charges were dismissed.

Equally important, after the witch trials were shut down in Salem in the summer of 1692, no one was ever executed for witchcraft anywhere in America again. Meanwhile, in England, witch trials continued and witchcraft was not decriminalized until 1727. To peg that date to an American benchmark, in 1727, Benjamin Franklin was 21 years old and already writing pamphlets on freedom.

The real history is not easy to uncover, even in Salem, where witch trial tourism is a huge boost to the local economy. (The town slogan is “Stop by for a Spell”).

But what we think we know about the Puritans in general and the Salem witch trials, in particular, comes from some dubious sources, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, the Salem-born American writer who was a descendant of an early Puritan family. Hawthorne’s great-grandfather had been one of the judges at the Salem witch trials, which was a huge public relations problem for him because of the general shame associated with the trials. To get around it, he changed the spelling of his name. Then, he wrote damning portraits of the Puritan founders of Massachusetts, which helped to distance him from his forebears—and, incidentally, to boost book sales.

This time of year, some secular writers routinely re-tell the witch trials story as one of religious hysteria, blaming the deep faith of the Puritans rather than the virtually universally held superstitions of the times.

Some contemporary Puritan scholars believe that Salem marked an intellectual turning point for the early Americans. Going forward after the trials, the colonists were forced to admit they’d made a horrible error, despite their commitment to creating a new and more moral society.

Historian Paul Johnson noted that in the months following the Salem witch trials, the General Court of Massachusetts passed a motion condemning the Salem judges. The families of those who were hanged were paid compensation and most of the members of the jury signed statements of regret. Many of those who had falsely testified against the victims confessed to perjury.

Samuel Sewall, one of the judges in the witch trials, almost immediately repented his involvement. Churches in Salem convened for days of penance and fasting, a practice that continued annually in Salem churches for years. Richard Francis, Sewall’s biographer, writes that Sewall’s own penance for his involvement in the witch trials was dedicating the rest of his life trying to eradicate slavery in America.

Of course, none of this compensates for the community compliance with the hysteria and mob violence that allowed the Salem witch trials and resulting executions to occur. Still, the American colonies were far ahead of the rest of the Western world at the time in confronting and dismissing superstition.

Their immediate repentance and reparations shows they didn’t hold themselves to a European standard. Instead, the people who had committed to building that “shining city on a hill” when they first landed in the Massachusetts Bay, held themselves to a standard that was higher than anyone in the world had yet seen.

They didn’t realize they were building what would become America, but they did know that their task was to create a place that would come to be called exceptional.